Viewpoint

Demand for AI and data processing is growing exponentially:

which role does the Netherlands want in the European data centre market and how much can it take on?

November 28, 2023 10 Minute Read

Looking for a PDF of this content?

The global demand for data centres is growing, propelled by the increasing use of data and artificial intelligence (AI). In recent decades, the Netherlands has become one of the most important data hubs on the planet. A robust digital economy is essential for the Netherlands’ competitive position, but inconsistent regulations and pressure on energy infrastructure pose challenges and bring social debate in their wake. Fact is that data usage is set to increase, as is the demand for data centres designed to facilitate data storage and processing. Data centres are power hungry, but that said, new developments on the data centre front may also have a role to play in energy transition. To secure sustainable and future-proof data supply and maintain the Netherlands’ attractive competitive position, the government needs to come up with a clear long-term national plan.

The Netherlands is in the front line when it comes to the growing demand for AI and data processing.

Global demand for data centres is growing, driven by several factors, including an increase in the use of data and AI. The latter, fuelled by language models like ChatGPT and GPT-3, is driving demand for data centres. This growing demand for storing and processing data is not limited to frequently used tools like search engines and recommendation systems used by streaming services. AI is commonly used in various sectors, such as horticulture and healthcare, to make processes more efficient. Since 2017, the volume of data has doubled every two to three years. AI is expected to propel the demand for data centre capacity in Europe to unprecedented heights, which is what we are currently witnessing in the United States.

The road to becoming a digital hub in Europe has not been smooth

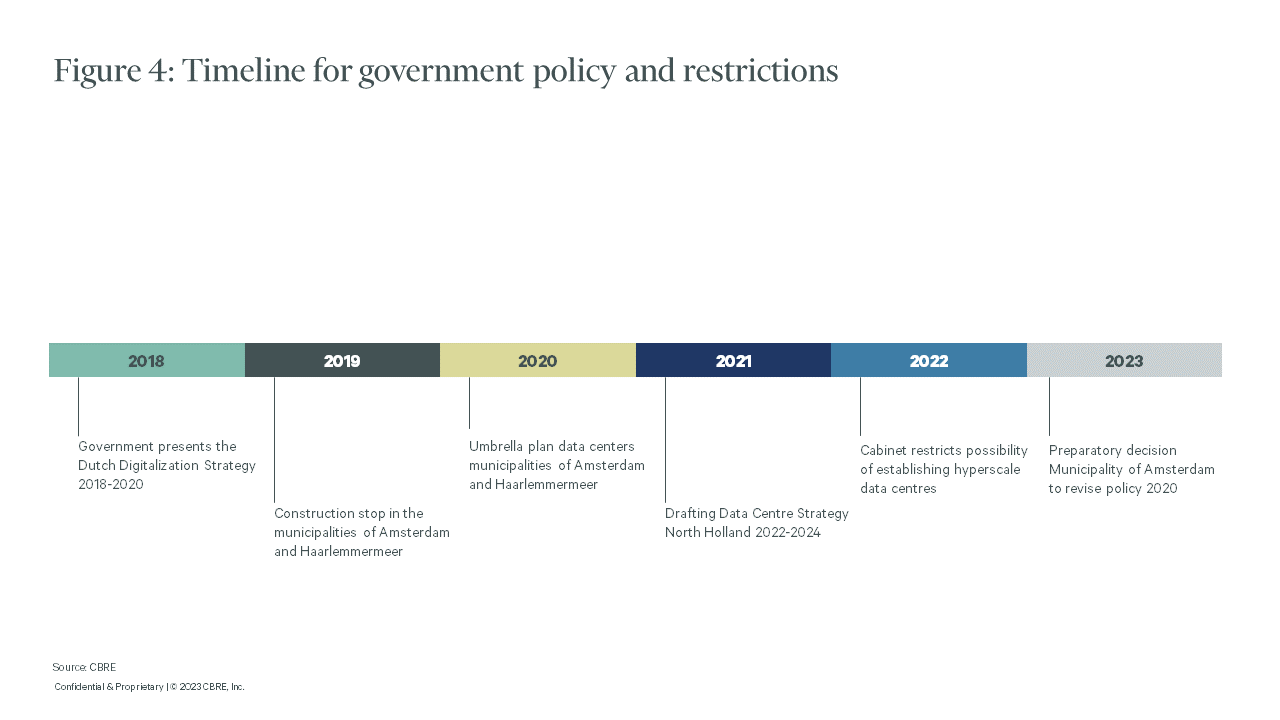

The government has been encouraging the development of data centres in an attempt to make the country the ‘digital leader’ in Europe. In its 2018-2021 Digitalisation Strategy, it has also underscored the importance of high-quality digital infrastructure to be able to compete with China and the States. Data centres are a key part of this digital infrastructure and the government has classified them as vital infrastructure. This means that data centres of a certain size are subject to the Dutch Investments, Mergers and Acquisitions (Security Screening) Act.

Rapid developments in the number of data centres between 2012 and 2018 have sparked discussions about the potential impact of data centres on the power grid, resulting in a sudden moratorium in 2019 in the municipalities of Amsterdam and Haarlemmermeer. This decision came as a surprise to data centre developers, occupiers and investors, all of whom are part of an internationally oriented market. The market in the Netherlands was put on the back burner while these organisations started to focus on other markets in Europe. The effect of this can currently be seen in the number of new developments. Supply in the Amsterdam data centre market is expected to increase by 15% from 2021 to 2024, while the rest of the FLPD markets collectively increase by 61% over the same period.

Not only that, the moratorium did not have the desired effect of stopping data centres from being built in the vicinity of Amsterdam and Schiphol. Local developers put forward new data centre initiatives to the surrounding municipalities where there was no construction freeze in place at that time. Considering that the power grid is not limited to municipality level, this was considered undesirable and the province of North Holland drafted a data centre strategy for the province as a whole.

The shift to digital working during the corona pandemic revealed the dire need for a properly functioning digital infrastructure. The municipalities of Haarlemmermeer and Amsterdam jointly produced a 'Data Centre Umbrella Plan', which clearly indicated where data centre developments are still possible and the amount of capacity that can be added up until 2030. Partly because of this and the increase in grid capacity in the area, more data centre initiatives are once again gathering momentum in quick succession. We expect the current supply to double in size (in MW) within the coming 3 to 5 years. However, on 9 November 2023, the Municipality of Amsterdam presented a new preparatory decision that revises the 2020 siting policy and proposes a new 12-month construction freeze. This will have limited impact on the projected growth of the market, but again creates uncertainty among market players about where they stand in the long term.

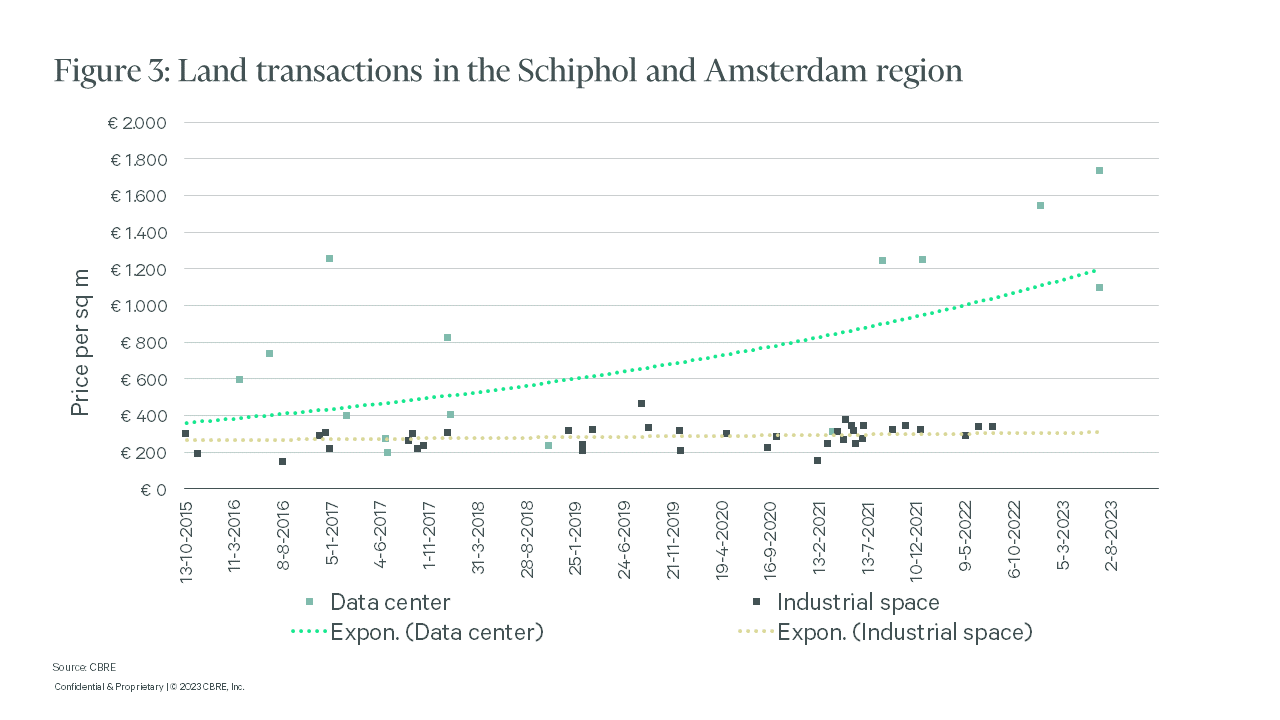

Extreme rise in land value of data centres in the Amsterdam/Schiphol region

The increase in regulations and limited energy supplies have led to scarcity and a significant rise in land values. What is striking is that, due to the sudden construction freeze in 2019/2020, only one land transaction for a data centre was made in the Amsterdam region. The ‘data centre umbrella plan’, which the municipalities of Amsterdam and Haarlemmermeer published in 2020, brought more clarity and identified specific pieces of land as potential data centre development sites. Several data centre developers, who already had a data centre based in the Netherlands before 2019/2020, subsequently resumed taking land holdings for data centre developments. Back in 2017, land intended for data centre development was still going for a price per square metre of between €200 and €400, compared to a price per square metre of between €1,500 and €1,700 in 2022/23. By comparison, land for logistics and industrial developments has fetched an average price per square metre of €290 over the same period.

Competition to find suitable data centre sites in the region due to the scarcity – thanks to legislation – is ratcheting up to this pressure on prices, even though financing and construction costs have skyrocketed.

In recent years, it has not only been local and provincial governments who have got involved in the establishment of new data centres. The municipal authorities approved Meta’s plans to build a large data centre in Zeewolde, but the government subsequently thwarted these plans. Exacerbating the situation, the government introduced legislation in 2022 to put restrictions on the construction of hyperscale[3] data centres. The thinking behind this was that large-scale data centres would take up too much space and use too much energy. As a result, the construction of hyperscale data centres has since only been possible in the municipalities of Hollands Kroon (North Holland) and Het Hogeland (Groningen) due to their location on the periphery of the country and their access to renewable energy. The precise policy for hyperscale data centres is currently being worked out in detail and the decision is expected to be left to the new government. The current moratorium for data centres requiring 70 MW or more is fanning uncertainty among users and developers, so investment decisions are currently being moved to other markets in Europe that can offer certainty.

[3] The government defines ‘hyperscale data centres’ as data centres covering more than 10 hectare and requiring energy supplies of 70 MW or more.

Data centres present opportunities for energy transition

Even though data centres consume a lot of electricity, they also offer an opportunity to contribute to the energy transition. Data centres have the potential to provide constant residual heat that could, for instance, supply homes in the Netherlands with heat using heat pumps that do not burn natural gas. In this way, the (mostly) renewable energy that data centres consume is partially returned, which is a more efficient use of energy.

Some of the data centres are already doing so, for example at the Van Nelle factory in Rotterdam. With the current energy transition in mind, this is an opportunity that can be exploited on a larger scale. There are currently around 28 residual heat initiatives in the Netherlands that are using data centres as a supplier of residual heat. In this respect, the Netherlands is far further down the road than other countries in Europe. The biggest challenge in this is finding the right balance between the capacity of data centres and the demand for heat in the immediate vicinity, so that a sustainable contribution to society’s energy needs can be made. The government must take control.

Clear government policies are needed if we are to meet the burgeoning demand for data centres and to maintain the country’s position as one of the continent’s digital hubs. Over the years, a lack of coordination has surfaced in the discussions between central and local governments, as we saw in Zeewolde in 2022 or, more recently, the disagreement between the Municipality of Uithoorn and the province of North Holland. The current policy for establishing data centres is proving to be inadequate and has resulted in a situation whereby developers are hopping from one municipality to another in their search for more favourable conditions. It has even led to a situation in which data centre developers, occupiers and investors no longer see the Netherlands as an attractive place to base themselves. With a view to putting residual heat to the best possible use, which could promote energy transition, this raises the question of whether the current designated locations for establishing a business are the most appropriate.

It is clear that the digital economy is crucial to the Netherlands and that digitalisation is not a transitory trend. More and more political parties are recognising the importance of this and are even talking about having a Ministry of Digital Affairs. The time has come to lay down a clear national policy on the future of the digital infrastructure in the Netherlands. In the absence of a long-term national plan, the Netherlands will lose its position as a digital hub in Europe to other countries.